[This article, which is a collaboration between Scott Rosenberg and Mark Follman, originally appeared on the Atlantic’s website. Since then it has been the subject of a MediaBugs error report filed by Frank Lindh. Yes, at MediaBugs, not only do we eat our own dogfood, we find it tasty!]

It is hard to describe the interview that took place on KQED’s Forum show on May 25, 2011, as anything other than a train wreck.

Osama bin Laden was dead, and Frank Lindh — father of John Walker Lindh, the “American Taliban” — had been invited on to discuss a New York Times op-ed piece he’d just published about his son’s 20-year prison sentence. The moment host Dave Iverson completed his introduction about the politically and emotionally charged case, Lindh cut in: “Can I add a really important correction to what you just said?”

Iverson had just described John Walker Lindh’s 2002 guilty plea as “one count of providing services to a terrorist organization.” That, Frank Lindh said, was simply wrong.

Yes, his son had pled guilty to providing services to the Taliban, in whose army he had enlisted. Doing so was a crime because the Taliban government was under U.S. economic sanctions for harboring Al Qaeda. But the Taliban was not (and has never been) classified by the U.S. government as a terrorist organization itself.

This distinction might seem picayune. But it cut to the heart of the disagreement between Americans who have viewed John Walker Lindh as a traitor and a terrorist and those, like his father, who believe he was a fervent Muslim who never intended to take up arms against his own country.

That morning, the clash over this one fact set host and guest on a collision course for the remainder of the 30-minute interview. The next day, KQED ran a half-hour Forum segment apologizing for the mess and picking over its own mistakes.

KQED’s on-air fiasco didn’t happen randomly or spontaneously. The collision was set in motion nine years before by 14 erroneous words in the New York Times.

This is the story of how that error was made, why it mattered, why it hasn’t been properly corrected to this day — and what lessons it offers about how newsroom traditions of verification and correction must evolve in the digital age.

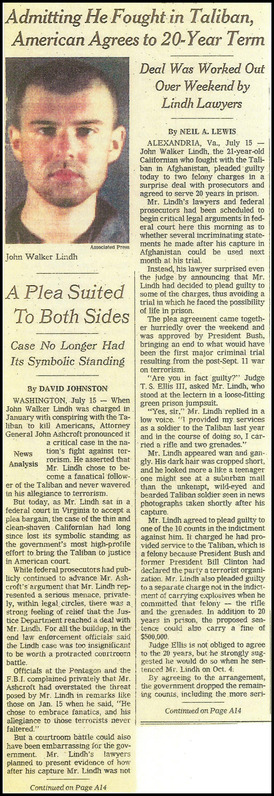

Lindh was a 20-year-old American citizen who turned up in Afghanistan in November, 2001, in the wake of a bloody, chaotic prison uprising in Mazar-i-Sharif. His story gradually emerged: He’d grown up in Washington, D.C., and California, converted to Islam in 1997, and in 2000 moved to Yemen and then Pakistan to study at a madrasa. Some time in spring 2001 he crossed the border to Afghanistan. There, he enlisted in the Taliban army, which was then engaged in a civil war with the warlords of the Northern Alliance, and trained at an Al Qaeda-funded camp.

All this preceded 9/11. By the time Lindh was captured, President Bush had declared a “global war on terror,” and the young man became a lightning-rod for public outrage in the U.S. In February, 2002, the Justice Department loudly unveiled 10 charges from a federal grand jury against him, most of them terrorism-related. But in a plea deal five months later, Lindh admitted only to having violated U.S. law by serving in the Taliban army and carrying weapons while doing so. Prosecutors dropped all the other charges.

Neil Lewis, a New York Times legal correspondent based in the D.C. bureau, covered the case and filed the paper’s front-page, 1,500-word piece on the guilty plea. In that July 16, 2002, story, Lewis wrote:

“Mr. Lindh agreed to plead guilty to one of the 10 counts in the indictment against him. It charged he had provided service to the Taliban, which is a felony because President Bush and former President Bill Clinton had declared the party a terrorist organization.”

The final 14 words of this passage — which KQED relied on, nine years later — were inaccurate. Neither president, Bush or Clinton, had ever formally declared the Taliban to be a terrorist organization. The State Department maintains a special list of entities that the U.S. considers to be terrorist groups. Though the Taliban has been subject to a variety of serious economic sanctions since 1999, when Clinton first put it on the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control list, it has never received official designation as a terrorist outfit. (This Metafilter thread discusses some possibilities why.)

Today, the now-retired Lewis says he can’t recall how he made the error: “I don’t remember whether it was my mistake or an editor’s, or something that a prosecutor might’ve told me.”

Lewis says no one pointed the error out at the time. And Frank Lindh didn’t bring it to the Times‘ attention then, either: “At the time it was originally published,” Lindh says, “my family and I were extremely preoccupied.”

So the error sat in the Times archive for nine years, until KQED unearthed it.

In the summer of 2002, of course, many Americans had little patience for arguments about the Taliban’s status as a terrorist organization. The Taliban had given Al Qaeda a haven; Al Qaeda had attacked the United States; did anything else matter?

But the question mattered profoundly to Lindh and his family. “It is no small thing to accuse a person of being a terrorist, or of providing assistance to or conspiring with a terrorist organization,” Frank Lindh says. “It’s basically calling the person a murderer.” His son, John, maintained that his purpose in joining the Taliban army had been to defend Muslim civilians from attacks by the insurgents who would later come to be known as the U.S.-allied Northern Alliance.

The record of the Lindh legal proceeding shows that federal prosecutors wanted very badly to hang the “terrorist” label on Lindh, but they couldn’t: either they didn’t have the evidence, or they had some other reason to drop all of the terrorism-related charges. As New York Times Justice Department correspondent David Johnston reported in a front page companion piece to Lewis’s story on July 16, 2002, U.S. officials “had grown skeptical that Mr. Lindh played any meaningful role in Islamic terrorism.” They allowed Lindh to limit his guilty plea to two violations of the Taliban economic sanctions.

Lindh’s statement to the court carefully maintained this distinction. He said: “I provided my services as a soldier to the Taliban last year from about August to December. In the course of doing so, I carried a rifle and two grenades. I did so knowingly and willingly knowing that it was illegal.”

Lewis’s mistaken description of the Taliban as a federally sanctioned terrorist organization was therefore far from a minor detail. For Lindh and his sympathizers, it was the crux of the story.

Moreover, the nature of Lindh’s crime and punishment was precisely what KQED’s Forum had planned to focus on — until the Times‘ error got in the way. “It definitely affected the tone of the show and derailed us,” says Dan Zoll, a senior producer for KQED. “Especially because this was such a high-profile case, I was definitely surprised to find that such an important fact had been incorrect.”

After the KQED show hoisted the mistake into the spotlight, MediaBugs, an online service for recording and fixing problems in news coverage, filed an error report and contacted the Times about the matter. And within a week, the Times had corrected the error — in a way.

If you look up that July 16, 2002, story today, you find the words “correction appended” inserted, a little awkwardly, between the byline and the first paragraph. And if you press “next page” three more times to get to the conclusion of the story and scroll all the way down, you’ll find the following notice:

“Correction: This article gives an imprecise explanation for why providing assistance to the Taliban was a felony. Executive orders by Presidents Bill Clinton and George Bush forbade such assistance because the Taliban was considered a threat to the United States and had provided haven to Al Qaeda, but those orders did not declare the Taliban to be a terrorist organization. (The error was brought to The Times‘s attention after related news reports in June 2011.)”

One might quibble with this wording’s halfhearted walk-back: After all, the article’s explanation wasn’t “imprecise” — it was wrong. But correction notices have a long history of defensive phrasing; minimizing your missteps is human nature. The main thing is that the Times noted, and corrected, its goof.

Yet the paper did not edit the story’s original text to reflect the correction. The same erroneous 14 words still sit, live, on the Times‘ website. To learn that they’ve been superseded, you have to click through three more pages. (Or, if you’re really unlucky, Google might send you to a different version of the same story that shows no trace at all of any correction.)

Philip Corbett, the Times‘ associate managing editor for standards, explained in an email, “For practical and technical reasons in this case, we decided simply to append the correction, rather than trying to rewrite a passage in a nine-year-old article.”

Is that enough? Corrections expert Craig Silverman, author of the book and blog “Regret the Error” and Columbia Journalism Review columnist (he is also an adviser to MediaBugs), doesn’t think so.

“If you only read the first two pages of that story,” Silverman says, “you’re not going to get to the correction, and you’re going to get the mistaken piece of information, and so it’s just not effective. That’s a very long article. What percent of people are going to read to the end of that and get to the correction, or even know that ‘correction appended’ means that it’s necessarily on the exact last page? The basic principle of ‘Let’s make sure that this error stops spreading’ is not really being upheld here.”

Institutions like the Times honed their correction practices in the age of print, when appending a notice was the best feasible option. But an always-available digital page is also always editable — and is part of a rapidly evolving news ecosystem in which stopping the spread of misinformation is more important than ever. Post-publication edits can uphold that principle without being furtive or seeming to rewrite history. Any changes to long-published articles can be made transparently, either in the text of an accompanying correction notice or in an archive of previous story versions.

The New York Times has maintained a useful, comprehensive website for 16 years now. Today, the digital edition is already eclipsing the paper product as its primary distribution channel. But in the digital age, serving as “paper of record” carries new burdens. It’s long past time for the Times, as the acknowledged leader of the verifiable-and-accountable wing of the American press, to take more active responsibility for the facts in its custody.

In American newspaper journalism, the New York Times sets the standard for commitment to accuracy — notwithstanding its well-known missteps of the last decade, from Jayson Blair’s fabrication to its Iraq war weapons-of-mass-destruction coverage. “The Times puts more energy and resources into corrections than probably any other news organization out there,” says Craig Silverman.

The newspaper’s commitment to fixing even tiny errors has opened it up to mockery over the years. Here’s Michael Kinsley, writing in 2009 (in, er, the Washington Post): “Who can take facts seriously after reading the daily ‘Corrections’ column in the New York Times? … the facts it corrects are generally so bizarre or trivial and its tone so schoolmarmish that the effect is to make the whole pursuit of factual accuracy seem ridiculous.”

For all the Times‘ dedication to its corrections page, however, the Times policy on correcting older errors is deeply inconsistent, if not outright whimsical. The paper doesn’t correct hoary old errors — except when it does.

In 2009, for example, the paper corrected a 1906 story about a secret inscription in Abraham Lincoln’s watch. And in another case that the paper itself had celebrated two days before KQED’s Lindh broadcast, the Times corrected an obituary from 1899 that had, among other errors, misspelled the deceased’s first name. That 1899 article is only available online in the form of a scanned image, so there’s no way the Times could update the original text with corrected information. Instead, the correction took the form of a column by James Barron, chronicling an elusive hunt to verify the details of Lt. M.K. Schwenk’s life story.

In Schwenk’s case, the Times was willing to re-report facts from over a century ago. As Barron declared, “It is never too late to set the record straight. If journalism is indeed the first rough draft of history, there is always time to revise, polish and perfect.”

But is there? Speaking for the Times, standards editor Corbett says there’s a limit to how much we should expect of the paper in the set-the-record-straight department.

“We have not established hard and fast rules on handling old corrections like this,” Corbett says. “But as a practical matter, we need to devote our limited time and resources primarily to fixing and correcting today’s or yesterday’s mistakes — and ideally, to preventing tomorrow’s mistakes. It can be very difficult to devote the time and effort to chasing down or re-reporting possible errors from five, ten or fifty years ago.”

That’s indisputable, as Barron’s tale illustrates. But it raises a dilemma for any paper, like the Times, that aims to be conscientious about the factual record. When the Times fixes “today’s or yesterday’s mistakes,” it does update the text to reflect the correction. At some point between “yesterday” and “five, ten or fifty years ago,” the paper stops doing so — it leaves mistakes like Lewis’s Lindh error in circulation.

Corbett admits that the Times has not drawn any “bright line” to set an expiration date on correctability in its archives, but prioritizes more recent errors. “In the case of the Lindh correction,” he says, “we made an exception because the error had arisen currently in a public, newsworthy context.”

You can sympathize with Corbett, and newsroom managers everywhere shuffling limited staff and resources, as they contemplate opening up countless stories in decades-deep archives to fine-tooth-comb reappraisal. Unlocking such a Pandora’s box of incertitude is daunting. It demands bravery and vision.

But it can’t be dodged. The Web, and its search tools, have made it inevitable. The dust of the old paper-clipping morgue, the wind-and-rewind crawl of the microfilm reels, and the costly metered searches of the Lexis-Nexis era are gone, and decades-old information is as easily accessible online as today’s headline.

In this world, where the noise and pace of news keeps accelerating, an archive like the Times‘ is more widely relied upon, and more valuable, than ever before. “We do try to do as much original reporting as possible, but for doing multiple topics a day, we often rely on sources like the New York Times,” says KQED’s Dan Zoll. “It’s unusual for that to backfire on us.”

Such a resource can no longer be treated as a static repository of established fact. As its errors continue to surface, its guardians must accept the responsibility of repairing them effectively. Otherwise, they’re telling us there’s a statute of limitations on their commitment to truth.

Journalists tend to be confident that most of their errors are efficiently caught and corrected. As New York Times managing editor and incoming executive editor Jill Abramson recently put it, “In the online world, the chances of a serious error in The Times going unnoticed or uncorrected are pretty slim.”

The Lindh story suggests otherwise. Unfortunately, the best research we have on the matter paints a different picture, too. Scott Maier, a professor at the University of Oregon, put the work of 22 newspapers under the microscope and found that “59 percent of local news and feature stories were found by news sources to have at least one error.” A followup study found that only two percent of those stories were ever corrected.

You can argue these numbers down a bit by quarreling with Maier’s approach, but it’s hard to avoid concluding that there are far more uncorrected errors in the press than most journalists believe. And you can buttress that conclusion by asking yourself how many errors you found the last time you — or your company, your neighborhood, your profession, anything that you’re deeply knowledgeable about — got covered by the media. While many of these errors are indeed trivial, you can never be certain today what sort of error will prove non-trivial tomorrow (as the U.S. State Department found when it failed to apprehend Christmas bombing suspect Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab because his name had been misspelled).

It’s reasonable, then, to assume that the New York Times‘ Lindh error, far from being a rare and isolated case, represents an iceberg-tip of inaccuracy. What, if anything, can editors do to steer clear of this disaster-in-waiting?

For starters, they can demonstrate that they invite and welcome pointers to potential errors from readers. Today’s stance — “we’re willing to consider fixing our mistakes if you hunt down our contact information and pester us” — is too passive. But it can be upgraded to an active pursuit of truth via some simple interface changes on a news website. Put a button on every page of every story, current and archived, that says “Report an error” — and then follow up on what the public tells you. Think of this as a customer service feedback loop, or a quality-control system. That’s how the most efficient large businesses that produce software or cars run their operations today; surely the information we use to run our society deserves at least as much care.

At this point, newsroom veterans are surely rolling their eyes: There’s no money in our budget for covering the state house, and you’re talking about fixing old errors?

Certainly, it’s hard to plan foundation work when the roof is about to cave in. But you can’t put the work off forever, either. Public trust in the product of journalism has been sinking for decades. If there’s any hope of reversing the trend, it could begin with an active commitment to finding and fixing errors like the Times‘ Lindh mistake, no matter how old they are — and before they cause more damage.

Silverman’s back-of-the-napkin guess is that such an expansion of the corrections mandate might consume 20 hours a week of a New York Times employee’s work. It could well be more than that — costly, yes, but neither infinite nor unmanageable. Any such effort would bear steady returns in bolstered public confidence. If that isn’t priceless, then why stay in the news business at all?

Report an error

Report an error

The tips of iceberg can be quite large. As large as small mountains, in fact. The failure to make corrections in those archived articles means errors and misinformation can be referenced in perpetuity. Therefore, other topical reports may repeat the error using the error-laden original was used in research to write the article. Reading requires critical thinking. And the nose of a bloodhound.