Today, the Knight Foundation released a comprehensive report evaluating the class of Knight News Challenge winners of which MediaBugs was a (happy and grateful) part.

The report has plenty of food for thought about the challenges MediaBugs faced and the efforts we made to overcome them during the two years of our grant.

Its appearance is a good opportunity also for us to share the topline summary of our final report to Knight. We filed this a while ago and I meant to post it sooner. Here it is, in the interest of transparency, for those who’d like to hear the full version of how our wins and losses looked from our perch here!

At the end of 2011 MediaBugs is pivoting from a funded project to a volunteer effort. We’ve racked up some considerable successes and some notable failures. Here’s a recap covering the full two years of project funding:

Successes:

* We built and successfully launched first a Bay Area-based and then a national site for publicly reporting errors in news coverage. These projects represented a public demonstration of how a transparent, neutral, public process for mediating the conversation between journalists and the public can work.

* We surveyed correction practices at media outlets both in our original Bay Area community and then nationally and built a public database of this information.

*We built and maintained a Twitter account with approximately 500 followers to spread awareness of both MediaBugs itself and other issues surrounding corrections practices.

* We maintained our own MediaBugs blog and contributed frequently to the MediaShift Idea Lab blog, where our posts were selected by the 2011 Mirror Awards as a finalist.

* We led a campaign to improve those correction practices in the form of the Report an Error Alliance, collaborating with Craig Silverman to promote the idea that every story page should have a button dedicated to inviting readers to report the mistakes they find. The practice has gained some momentum, with adoption at high-traffic websites like the Washington Post and the Huffington Post.

* We handled 158 error reports with the two largest outcomes being closed: corrected (59) and closed: unresolved (68). Those results included corrections across a range of major media including The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, USA Today, Fox News, CNN, National Public Radio, CBS News, the Associated Press, Reuters, Yahoo News, TechCrunch, and others.

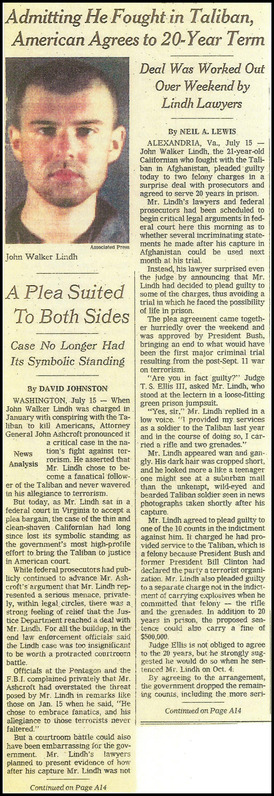

* We took one high-profile error report involving “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh, KQED, and the New York Times, and used it as a kind of teachable moment to publicize some of the problems with existing corrections practices as they collide with digital-era realities. Our extended effort resulted in the Times correcting a story that the subject (through his father) had failed to get corrected for nearly a decade. The full write-up of this story was published on The Atlantic’s website in July, 2011.

* Our surveys of correction practices and related public commentary led many news outlets to revamp and improve their procedures. And many of the specific error-report interactions that led to corrections helped shed light on formerly closed processes in newsrooms, leaving a public record of the interaction between members of the public who brought complaints and journalists who responded to them.

* We partnered with other organizations, including NewsTrust and the Washington News Council, on efforts to correct inaccuracies in news coverage and establish regional MediaBugs organizations. Our software platform became the basis for Carl Malamud’s Legal Bug Tracker project.

Failures:

Our single biggest failure was our inability to persuade any media outlet with a significant profile or wide readership to adopt our service and install our widget on their pages. This limited our reach and made it difficult to spread our ideas. Users had to know about our service already in order to use it, instead of simply finding it in the course of their media consumption.

Our efforts to solve this problem — outreach to friends and colleagues in media outlets; public and private overtures to editors, newsroom managers, and website producers; back-to-the-drawing-board rethinks and revamps of our product and service — occupied much of our time and energy through the two years of the Knight grant.

We did find some success in getting MediaBugs adopted by smaller outlets, local news sites and specialty blogs. In general, it seemed that the people who chose to work with us were those who least needed the service; they were already paying close attention to feedback from their readership. The larger institutions that have the greatest volume of user complaints and the least efficient customer feedback loops were the least likely to take advantage of MediaBugs.

We identified a number of obstacles that stood in our way:

* Large news organizations and their leaders remain unwilling even to consider handing any role in the corrections process to a third party.

* Most newsroom leaders do not believe they have an accuracy problem that needs to be solved. Some feel their existing corrections process is sufficient; others recognize they have a problem with making errors and not correcting them, but do not connect that problem with the decline in public trust in media, which they instead attribute to partisan emotion.

Our other major failure was that we never gathered the sort of active community of error reporters that we hoped to foster. Our efforts included outreach to journalism schools, promotion of MediaBugs at in-person events and industry gatherings (like Hacks and Hackers and SPJ meetups), and postings at established online community sites whose participants might embrace the MediaBugs concept. But our rate of participation and bug-filing remained disappointing.

One explanation we reluctantly came to consider that we hadn’t originally expected: Much of the public sees media-outlet accuracy failures as “not our problem.” The journalists are messing up, they believe, and it’s the journalists’ job to fix things.

A final failure is that we have not, to date, made as much progress as we hoped in transforming journalists’ way of thinking about corrections. We imagined that public demonstration of a more flexible view of errors and corrections would encourage a less secretive, less guilty-minded, more accepting stance in newsrooms. But two years after MediaBugs’ founding, getting news organizations to admit and fix their mistakes in most cases still demands hard work, persistence and often some inside knowledge. Most of the time, it still feels like pushing a boulder up a hill. This needs to change, for the good of the profession and the health of our communities, and MediaBugs intends to keep working on it.

Report an error

Report an error